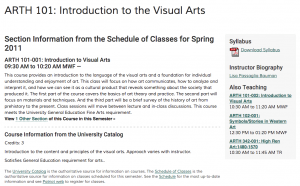

The vast majority of college course websites that I’ve encountered are essentially web-accessible versions of the course syllabus, perhaps with some additional content that the instructor (thankfully) resisted including in the hardcopy syllabi handed out on the first day of class. Maybe there are hyperlinks to some of the course materials, perhaps even some embedded videos. If students are lucky, the instructor includes links to lecture notes or PDFs of the slides presented each class. And it’s not unusual that the course website includes some sort of interactivity feature, such as a bulletin board forum type space for students to post reading responses, although in most cases these are shielded from the public by a system like Blackboard.

We have all seen, and many of us have made, the same old boring static course website, aka, the digital syllabus.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this model—most folks who implement course websites have created this type of online syllabus at some point in their teaching. However, it is worth noting that the possibilities for using the web for structuring a course extend well beyond the unidirectional model of the online syllabus or the semi-multidirectional model that includes student interactions in forums or blog posts.

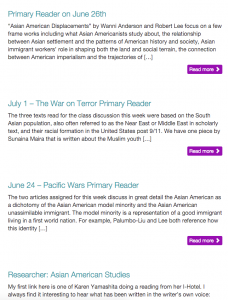

A growing number of instructors are devising ways to incorporate different modes of interaction and knowledge production in their course websites. One example is interactive blogging models where students are asked to fill different roles that might include things like summaries of assigned readings, analysis of current events (in relation to readings, of course), mini book reviews or film critiques, curating resources related to a class discussion or specific topic, creating annotated bibliographies on a topic, and responding to and fostering further discussion about their peers’ posts. The connective thread in all of these cases is that they all: 1) encourages students to engage with the texts and course materials beyond classroom discussions; 2) gets students engaging with each other in a format that allows them to take a moment to craft their responses rather than respond off the cuff like in seminars; and 3) results in original content (or curated resources) that give students’ ideas lives that exist beyond the duration of the course, for publics beyond their classmates.

Interactive multi-role course blogs are one way to give life to a course website.

I’m obviously not breaking new ground here. But I wanted to soapbox on this topic because starting the discussion, and framing it in terms of transitioning existing classroom pedagogies to digital spaces, might lead to further discussions of how digital platforms can function as more than just digital syllabi. And since the Digital Fellows and other groups within the CUNY digital scholarship ecosystem lead countless workshops on using web publishing platforms and building course websites, I feel it’s important to also comment on the possibilities for how those sites get used and the content that goes in them.

For wholly narcissistic and self-congratulatory reasons, I would also like to highlight one low-stakes example of what this might look like in practice. This past summer, I helped run a seminar for K-12 educators on Asian American film and literature through the lens of New York City. One of the requirements of the National Endowment from the Humanities as a condition of the program’s funding was that the seminar needed a website to inform potential participants about the seminar. Another requirement was for participants to complete some sort of final projects based on the seminar theme.

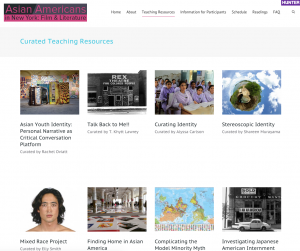

The other organizers and I decided that rather than simply put together a static web page hosted on a university website, we wanted something that would attract a broad range of applicants, but which would also serve as an enduring public resource for all of the educators who wouldn’t themselves be able to attend the seminar. Eventually, we decided that the final projects would be individually curated archives related to a theme of the participant’s choosing, which would include teaching resources, classroom activities, assessment guidelines, and anything else that might help other educators teach about topics related to the experiences, struggles, and cultural productions of Asian Americans and other immigrant communities within the U.S. Several participants were also asked to write short reflection pieces as part of a series of blog posts that were cross-published on the Center for Asian American Media website.

Curated teaching resources created by participants provide original content that endures beyond the course

Importantly, we wanted the teaching resources created by participants to be semi-autonomous resources that stand on their own outside of the context of the seminar, and which are easily searchable without having to dig through the seminar website to find it. To this end, we strongly encouraged participants to craft their curated teaching resources on external platforms. We recommended a couple of different third-party website hosting platforms, and now those sites are in the wild, but also included as part of the seminar portfolio. And for the few individuals who really weren’t interested in trying to build their own sites (many took it on as their first web creation challenge!), I had them assemble rich-text documents containing all of the content for me to publish on their behalf.

All of the materials produced by the participants are fantastic public resources that cover far more ground than we could have even attempted to cover in the two week seminar. When participants began the seminar, most of them had a strong desire to be able to better teach the types of topics we covered in the seminar, but felt underprepared and lacking in exposure to teaching materials and resources. The hope is that participants helped fill some of this void on the internet, and that they return to their teaching communities and share their newly created resources with their peers, and that other similar projects emerge in kind. You can view the seminar website, hosted on the CUNY Academic Commons, Asian Americans in New York: Film & Literature, or view the curated teaching resources directly.