Last time, I talked about some of the ways that scholars can get the most out of the search features of large collections of books that are available online. In this post, I will point out just a few of the smaller archives that are often better places to search.

For scholars in fields that deal with books as primary texts, large collections of digitized books can be a lifesaver; they allow quick access to millions of books from anywhere, and their search features make it easy to track down the sources of quotations. In many cases, however, it can be better to turn to more specialized web sites. Although large collections like Google Books, HathiTrust, and the Internet Archive are wonderful resources, they are put together through hasty means, without the care that scholarly editors take in reproducing historical texts. The word search features of all of these databases depend on computer-generated transcription of scanned pages, the results of which are often inaccurate for old, poorly printed, or unusually formatted texts. These collections are also organized somewhat haphazardly, and their metadata for texts (author names, publication dates, edition numbers, etc.) are often inaccurate. Fortunately, there are many other collections of primary texts out on the web that are much more carefully curated by scholars. The trouble, sometimes, is finding them.

Two databases that a lot of English-department people are familiar with are Early English Books Online (EEBO) and Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (ECCO), both of which are invaluable for working with texts prior to 1800. Those specializing in other languages might be familiar with Gallica (for French), Project Runeberg (for Nordic literature), or Perseus (which covers a variety of languages, including a large number of ancient Greek and Roman texts). These are fairly large collections, but they are focused on specific languages and time periods and maintained with much more care than Google Books. Many of them also have search engines that can account for some of the specific challenges that can occur in searching material from earlier time periods, including spelling variation.

Apart from these large disciplinary archives, there are many smaller archives out there that cover specific authors, regions, or types of text. You can find many of them of web sites that list online resources for scholars, including this one from U. Penn and this one from Western Michigan University. One list that deserves special mention is Voice of the Shuttle, a project run by Alan Liu at UC Santa Barbara; it is not totally up to date, but it shows the great variety of online scholarly resources that emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some of the sites listed in Voice of the Shuttle are now defunct, but it can still be a way to find useful sites that do not readily turn up in Google.

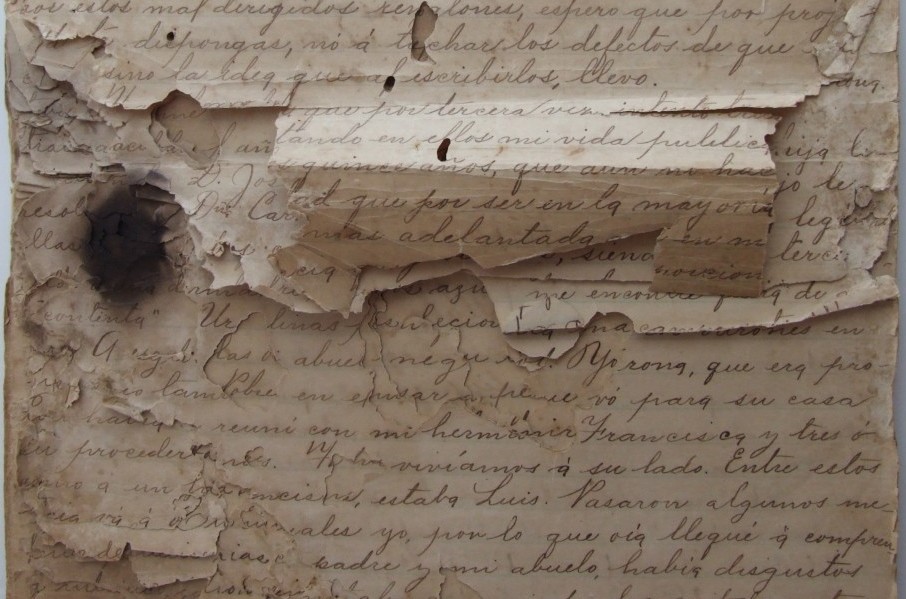

Many major literary authors have dedicated archives, which are often presented as editorial projects but which sometimes go far beyond what can be readily accomplished in a printed scholarly edition. Of particular importance are the Emily Dickinson Archive, which hosts page scans of Dickinson’s manuscripts, many of them manually transcribed; and the William Blake Archive, which serves the invaluable function of making it possible to compare the different editions of Blake’s illuminated books. Other collections more focused on historical documents include the Early Caribbean Digital Archive, the 19th-Century Schoolbooks collection from the University of Pittsburgh, the September 11 Digital Archive, to which several people at the Graduate Center contributed, and the Marilyn Gittel Digital Archive, which contains documents from one of the most important political scientists and activists to teach in the CUNY system.

The web is also home to a number of quirkier archives, many of which document the history of the Internet itself. UbuWeb is Kenneth Goldsmith’s archive of the avant-garde, including a wide variety of text, image, sound, and video files. Jason Scott’s Textfiles.com hosts a collection of files that circulated in the early days of the Internet. Oocities is an archive of GeoCities, a popular web hosting service that went down in 2009; it includes thousands of early personal web pages and all manner of strange things.

Image from Wikimedia Commons.