Last March, with support from the Publics Lab and the English program, we held an online roundtable discussion, Dissertation Futures. Led by Drs. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Marisa Parham, Kay Sohini, and Zoe LeBlanc, conversations centered on the forms and possibilities of dissertations beyond existing conventions. Building on Futures Initiative’s #remixthediss event that was held almost ten years ago (!!), we began with conversations about the current landscape of digital dissertations and discussed support and resources necessary for its growth and creative possibilities. In the following sections, we have provided a recap of the event and discussion.

Forms that digital dissertations can take

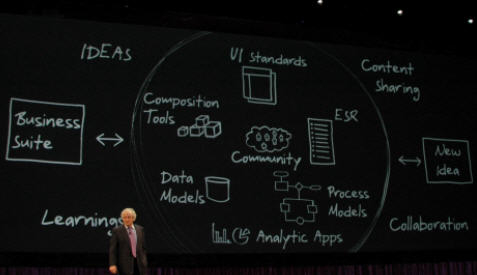

In thinking about the forms of digital dissertations, we were asked to consider what becomes of the dissertation as we move increasingly into a world where scholarly outputs don’t just look like journal articles and monographs. Digital dissertations open us up to multiple forms and methods, such as Justin Wigard’s video game dissertation, and these possibilities also transform how we ask questions. While the prospectus and dissertation often change even in conventional formats, Kathleen and Marissa suggest that the process towards a digital dissertation has to be and is more flexible as we move away from an expected end product of a written monograph. As Marissa notes, this serves as opportunities for marginalized communities and others to find forms that better speak to their interest beyond even what we are able to currently imagine.

Indeed, Kay’s dissertation in English was in the form of a comic, which she used to inquire and engage her themes. Utilizing the illustrative form, she was able to incorporate creative data visualizations through Tableau, connecting her personal stories to larger societal issues. Zoe’s digital history dissertation involved building a web application to extract data which she then digitized and analyzed computationally. While the end result was not fully digital, she reflects that her committee was keen and excited by her graphs and computational work. Importantly, Zoe notes that what gets defined as digital and alternative is contextualized against disciplinary and institutional norms, and her work pushes against the conventional normative space for what counts as scholarship in her department when she was completing her PhD. By comparison, in her current role at the School of Information Sciences, where her digital projects are not seen as unconventional.

As our speakers suggest, digital dissertations take multiple forms, and the expanding potential forms a digital dissertation may take also provides a space for doctoral candidates to combine scholarly purpose with form, opening up new questions. For example, the newness of a podcast format might prompt us to pause and think about the affective aspects of our research or data through the integration of background music or ambient sound. We can ask: how does sound serve our argument?

Approaching and working with committees and advisors

Some of the challenges we face as students and faculty venturing into digital dissertations echo Zoe’s sentiments early in the roundtable: new forms of scholarly production challenge conventional, normative expectations. To help students better prepare to produce new scholarly forms, our speakers suggest exposing students early in their degree to “low stakes” digital work in order to learn necessary skills. Gesturing to the need for a support network, Marissa suggests a modified approach to selecting a dissertation committee–one that begins before the proposal stage and identifies faculty who can support either the content or the form of your work. Doing so ensures that you have an ongoing support network throughout the dissertation process.

Pointing to Justin Wigard’s dissertation project, Kathleen explains that he began pursuing his interest in producing a scholarly video game for a dissertation while he was still completing his coursework. The early start helped him in identify supportive committee members for his digital dissertation, while also creating the time and space to practice and build necessary technical skills. Similarly, Kay shared that she began producing illustrated essays for her seminars that helped her explore what she was capable of early enough that she could refine her ideas before and during the proposal stage. While it would be optimal to start planning for the dissertation early on, not everyone is ready to do so during coursework. Nevertheless, exposure early on to technology tools and skills in the degree program, presenters agree, can help reshape and clarify the digital dissertation process.

On the topic of mentors, speakers agreed that a productive digital dissertation committee consists of folx who can provide mentorship in content and technical skills. We may be more familiar with locating expertise within our content interest but as the speakers suggested, it is equally important to find advisors who can support you in the digital methods and forms that you’re interested in. While this is not always possible, having a member on your committee who can be supportive of your exploration in digital tools will be helpful even if they may not have the exact technical skill set. For example, Marissa has reached out to folx in architecture to draw on their expertise and experiences in her projects. Ultimately, your committee and, more broadly, the community you build around your work will ideally be there to support you even when your dissertation isn’t at its prettiest. The dissertation isn’t made up of what constitutes an academic question but who is included in this academic question.

Sustainability and maintenance of work

Questions from attendees repeatedly raised issues of sustainability and maintenance of digital dissertations, something that Marissa and Zoe identified as particularly important. Existing infrastructures for scholarly work don’t support or work well with digital dissertations. Submitting digital projects to repositories like ProQuest can be challenging, and the pace of technology change can make it challenging to tell if long-term support exists or if the investment in learning the skill is going to be worth it. However, as Marissa suggests, overthinking about the future of sustainability runs the risk of holding you back from taking opportunities to be creative and experimental rather than making choices that lead to the best do the work you can and want to do.

Nonetheless, our speakers do suggest that creating a project with interoperability in mind (i.e. the ability for information to be exchanged and used across different systems and platforms) can help with our feelings of anxiety about the work’s future. For example, even for her more dramatic performative digital experimental projects, Marissa has backed them up to spreadsheets where the HTML version, text version, and screenshot for each page and movement were recorded. Hence, even if the current form is no longer supported in the future, the data is retained and archived for the possibilities of future versions, transformations, and rebirth.

Personally, I have shared similar concerns for sustainability, but leaning into the fact that digital dissertations are different forms in itself, this feeling of ephemerality seems to be a part of undertaking this form and as such, quite freeing. After all, when I look back at my own written work from when I published in my first year of graduate school, I am always tempted to revamp, refresh it. If we embrace that the digital dissertations as a form invites us to reconsider our form with our argument at different times and contexts, it keeps our scholarship alive and acknowledges that knowledge make-ing is an ever ongoing process.

Scoping the work

Speaking from a different perspective, Kathleen and Kay also call us to be attentive to thinking about sustainability in terms of our own labor. For many, the digital dissertation is really a two-part product, with the digital object and the written piece as separate work for a single deposit, which was exemplified in Zoe’s dissertation and Jesse Merandy’s Vanishing Leaves. This creates additional labor for the student, as even fully digital work is often expected to also have an accompanying whitepaper that discusses the process of creating the dissertation. With this in mind, considering where to draw the line on what goes in the dissertation and what can come after. For example, Amanda Visconti’s fully digital dissertation for Infinite Ulysses was originally proposed with two additional projects.

To get a sense of how we can scope our work, Zoe suggests looking for projects that are similar to what you intend to do and reaching out to the authors/makers of those work. Often the final output obscures some of the interpretive choices made and doesn’t necessarily reveal the time and labor involved in getting the project to where it is.

Publications and the academic job

While our event primarily focused on the dissertation, it ultimately also began to address the possibilities and challenges of academic scholarship and publishing beyond the written word. In part, the large variety of possibilities for digital and forms beyond the written word (e.g. a podcast v.s. a website) makes it challenging to fit into many established academic publishing guidelines and avenues, often leaving scholars of such work to either self-publish and/or write-up an additional piece that fits within the expectations of written publications. Folded into the question of publication is the discussion around evaluation and peer-review where it is often more challenging to do anonymous peer review for a digital project. As such, while there is much enthusiasm and excitement, our existing infrastructure has yet to catch up, leading to scholars feeling a little lost.

Ultimately, interwoven throughout the conversations is a clear theme that the digital dissertation, while seemingly the final product of a PhD education, has to be built into the undergraduate and graduate curriculum. Marissa has emphasized the necessary space and structure in the curriculum for faculty to incorporate low-stakes opportunities where students are invited to experiment with digital projects that builds not only their technical skills but also their fluency in a medium that currently exists for the written text. In diversifying the scholarship we consume, pursue, and produce, from individual faculty members, departments, college, and academic publishers, we are better able to support the work of doing digital dissertations.

Hence, if the only/main reason for doing a digital dissertation is the idea that it will provide us with more transferable skills to land us a job, it is probably insufficient. Rather, as our speakers have emphasized throughout the event, pursuing a digital dissertation is because it is a form that is right for the questions we ask and is more truthful to the work we want to produce and see ourselves in. Deciding whether to do it requires deep contemplation as the current landscape reflects enthusiasm while also currently building the necessary resources and infrastructure. At the same time, if digital and non-conventional forms are important, then waiting to do it after getting the tenure-track job can be an endless cycle of waiting (after all, getting the tenure-track job is just the first step towards full professorship).

In closing

As this event was open to publics beyond the GC and CUNY communities, we were also joined by students, faculty, and scholars from other institutions who were interested in this discussion, This is heartening to see as it signals a growing community of folx interested in supporting, pursuing and producing non-conventional forms of dissertations, projects, and scholarship. Echoing the calls for building communities and resources around such scholarship from students and faculty on the Zoom call, we have also created a beta version of a GC Digital Dissertation Resource Guide that has suggestions and resources for students and faculty. Our guide will also include a podcast series where we interviewed folx about their experience in mentoring, supporting, and/or doing a digital dissertation.

If you missed our event, you can rewatch our livestream on YouTube.