Introduction to 2 Part Series:

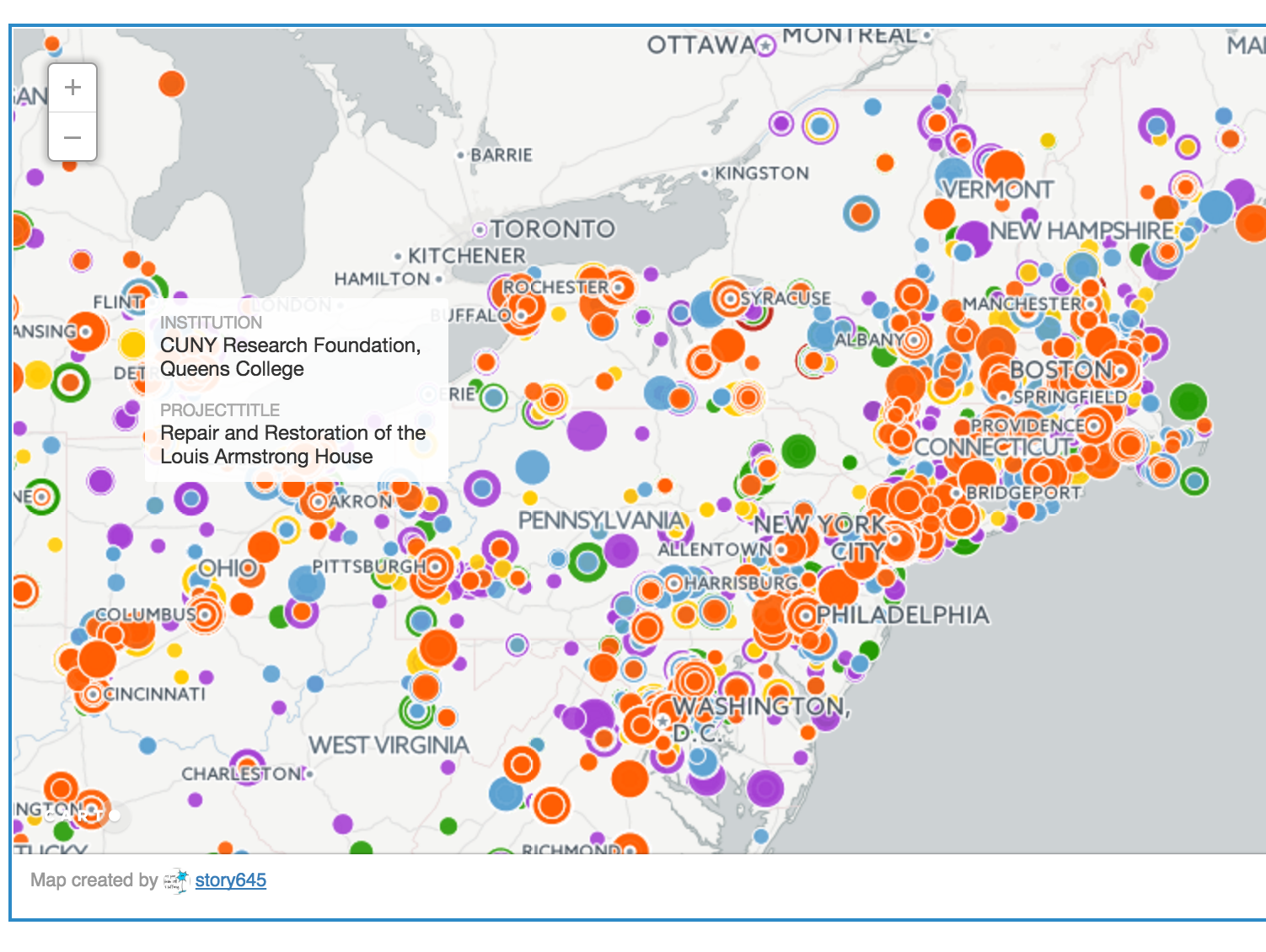

As of June 2017, about one quarter of the US population did not have access to broadband internet. This includes 16 million or 28% of rural residents, and 62 million or 23% of urban residents (1). Rates of connection vary widely by city; for example, 19% of NYC residents are unconnected compared with 40% of Detroit residents (2). In recognizing that internet access is vital to managing, navigating and participating in life in the 21st C, some communities and municipalities have taken up the challenge of providing access; one project maps over 800 initiatives (3). In reviewing just a handful of of these initiatives, I have found the variety of interpretations and understandings of, and ways of addressing access to the internet by grassroots community groups compelling.

The community and technical networks assembled by these grassroots groups are collectively referred to as “community wireless networks” (CWNs). Urban examples include NYC Mesh, Equitable Internet Initiative (Detroit), and PeoplesOpen.net (Oakland); there are also many rural-based collectives (see reference #3 for more information) as well as international examples (ex. Guifi.net in Spain).

This two part blog post series explores the efforts of 3 urban-based CWNs – those named above – highlighting the nuances of their understandings of access, which include but go beyond mere physical infrastructure and service provision. This inquiry reveals much about the challenges and possibilities embedded in these missed connections, and also has lessons for our own work.

Pt 1: Community Wireless Networks and Expanded Notions of Access

In thinking about “access”, infrastructure is a necessary baseline hurdle that CWNs must overcome. Some rural areas of the United States lack physical infrastructure all together, in part because it is not seen as a worthwhile investment by the companies that provide Internet access to the majority of US residents. Similar cost-benefit analyses have left dark fibers (areas where physical infrastructure exists, but service is not routed) or no infrastructure in urban neighborhoods as well. Infrastructure-related exclusions in Detroit and Cleveland have been referred to as “digital redlining” because access to broadband correlates with and compounds existing geographically-based racial and class inequalities. On behalf of these community members, one civil rights attorney filed complaints against the FCC in 2016 (4). More specifically, the “[civil rights attorney] and community members maintain that AT&T is withholding high-speed Internet from minority neighborhoods that have higher poverty rates” (5).

In addressing the lack of infrastructure, CWNs use mesh network technology. These communication systems involve a decentralized, “peer-to-peer” network of wireless routers that attach to members’ roofs and can send and share a signal between them. When this network is plugged into the internet backbone and routed through an internet exchange point, the entire network can access the internet as we might generally think of it (6). Mesh network technology also creates an intranet that can be used to communicate across the network even if they were to be cut off from internet access. This feature has been handy during natural disaster emergencies like in Red Hook, Brooklyn during Superstorm Sandy, and is framed as a resiliency-related feature by CWNs more generally (7).

CWNs and mesh network technology may be preferred by community members even when infrastructure and service is available. This preference is driven by concerns related to the impermanence of net neutrality, the increasing privatization and monopolization of internet service provision, and an evolving public discussion about data privacy, security, ownership, and use, which together highlights disadvantages for the consumer or end user. CWNs are sometimes seen as a way of gaining some control over one’s access to internet by cutting out the ISP’s mediation. Relatedly, CWNs seem to unanimously recognize the data ownership rights of their community members, which is evidenced in their commitments not to store, share, or sell information of members’ use of the internet or intranet.

Simultaneously, a preference for CWNs is often driven by an understanding that the internet – like water, heat, and housing – is a basic necessity that should be affordable and available to all. As Bill Callahan, director of the Detroit-based nonprofit Connect Your Community notes, “[internet access] is now no longer a problem of lost opportunity — this is a problem of a genuine barrier… In many ways you could say the cost of internet is a new poll tax. …This has now become a civil rights issue” (8). This understanding seemed to undergird the 2016 decision by a federal court that “affirmed the [then] government’s view that broadband is as essential as the phone and power and should be available to all Americans, rather than a luxury that does not need close government supervision” (9). The weight of this decision has since been eroded by decisions like the repealing of Net Neutrality by the FCC under the current administration (10).

Towards this end, CWNs are of low cost or no cost to members. For PeoplesOpen.net this involves free service, other than suggesting users purchase their own equipment if possible (one time cost of ~$100), while NYC Mesh asks for a $20-per-household monthly charge for households that can afford it. Both also accept donations to keep costs down. In addition some CWNs make other inclusive commitments clear – for example, NYC Mesh explicitly states they don’t require any information related to immigration or citizenship status.

“Access” is also tied to their participatory structures of governance and maintenance, and their efforts to build digital literacy in their communities. CWNs are understood to be community-owned entities, and in fulfilling that role they often hold community meetings and/or offer opportunities for users to get involved in the maintaining, growing, and governance of the project. To this end, NYC Mesh hosts monthly meet-ups, identifies roles motivated volunteers might fulfill, and makes its Slack channel (a chat-based communication platform) publicly available. Similarly, PeoplesOpen.net hosts workshops every few months and has a list of specific roles “that anyone (with the right motivation) can fulfill”. In this same vein, CWNs are generally transparent with how and where their infrastructure is set up and how its governed and managed – providing guides and tutorials on their websites and relying on open-source, publicly-available tools.

In sum, CWNs’ create a new digital economy that is shared, co-owned, and managed by members of the CWN. They employ non-discriminatory definitions of “who” can be a community member. They rely on and adapt the built environment in building their community. Their existence as a community brings into being an example of a community enacting internet access as a human right.

Taken together, their nuanced approach to access actively reworks the social, material, economic, and political relationships that govern the way the majority of us gain access to the internet. Marc Juul, a co-creator of PeoplesOpen.net suggests as much in describing a deeper meaning of “peer-to-peer” in mesh network technology: “What we’re trying to do is something horizontal, where everyone is part of the internet. Everyone is a node on the internet that makes it possible for the internet to exist. We’re really trying to not to get into the state of mind where people are thinking that the internet is delivered to them by someone else” (11).

In challenging these relations, community wireless networks inherently (and sometimes explicitly) challenge dominant, capitalocentric relations of power – with regard to internet provision and access and more broadly. Key to this challenge is the centering of the community and the re-framing of the individual end user as a part of a larger whole. Part 2 of this series further explore this active reworking of relationships, and the liberatory and emancipatory intention and potential therein.

REFERENCES

(1) The Urban Unconnected. A white paper by IHS Market and Wireless Broadband Alliance (WBA), June 2017: https://technology.ihs.com/api/binary/593374

(2) Detroit’s Broadband Infrastructure, Connectivity and Adoption Issues, a presentation by Mark Hudson of Rocket Filber, http://transition.fcc.gov/c2h/10282015/marc-hudson-presentation-10282015.pdf ; Unemployed Detroit Residents Are Trapped by a Digital Divide, by Cecilia Kang, NYTimes, May 22, 2016: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/23/technology/unemployed-detroit-residents-are-trapped-by-a-digital-divide.html

(3) Community Network Map, Created and maintained by Community Networks, a project of the Institute for Self-Reliance. https://muninetworks.org/communitymap

(4) The complaints are in response “to a report from the National Digital Inclusion Alliance and Connect Your Community group. Their analysis concluded that the disparities among neighborhoods are a product of over a decade of deliberate infrastructure investment decisions, resulting in digital redlining. Their well-documented maps help visualize these disparities among neighborhoods.” Slow AT&T Service Will Block Thousands of Cleveland, Detroit Households From Promised Access Discounts, Connect your Community, Blog, Sept 5, 2016: http://connectyourcommunity.org/slow-att-service-will-block-thousands-of-cleveland-detroit-households-from-promised-access-discounts/

(5) AT&T Accused of Digital Redlining in Detroit, a post by Matthew Marcus on the Community Networks website (a project of the Institute for Self-Reliance), October 18, 2017: https://muninetworks.org/content/att-accused-digital-redlining-detroit

(6) Understanding Mesh Networking Part 1, by Ram Ramanathan, In the Mesh, July 26, 2018: https://inthemesh.com/archive/understanding-mesh-networking-part-i/ ; Understanding Mesh Networking Part 2, by by Ram Ramanathan, In the Mesh, Aug 17, 2018: https://inthemesh.com/archive/understanding-mesh-networking-part-ii/ ; This is What the Backbone of the World’s Internet Looks Like, Vox, Oct 24, 2015: https://mybroadband.co.za/news/fibre/143334-this-is-what-the-backbone-of-worlds-internet-looks-like.html.

(7) Communities growing Detroit’s digital capacity one house at a time, by Ryan Grimes, Michigan Radio NPR, March 3, 2016: http://www.michiganradio.org/post/communities-growing-detroits-digital-capacity-one-house-time

(8) Detroit’s digital divide is leaving nearly half the city offline, by Trevor Bach, Detroit Metro Times, Dec. 6, 2017: https://www.metrotimes.com/detroit/detroits-digital-divide-is-leaving-nearly-half-of-the-motor-city-offline/Content?oid=7625861

(9) Court Backs Rules Treating Internet as Utility, Not Luxury, By Cecilia Kang, NYTimes, June, 14, 2016: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/15/technology/net-neutrality-fcc-appeals-court-ruling.html ; See official document here: https://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/3F95E49183E6F8AF85257FD200505A3A/$file/15-1063-1619173.pdf

(10) Net Neutrality Has Officially Been Repealed. Here’s How That Could Affect You, by Keith Collins, NYTimes, June 11, 2018: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/11/technology/net-neutrality-repeal.html

(11) Want to Guarantee Net Neutrality? Join Peer-to-Peer, Community-Run Internet, by Adele Peters, Fast Company, Dec 19, 2017: https://www.fastcompany.com/40509146/want-to-guarantee-net-neutrality-join-peer-to-peer-community-run-internet