“[…] the change may be illustrated by the difference between a craftsman of the old type, who selected the proper tool for a delicate piece of work, and the worker of today, who must decide quickly which of the many levers or switches to pull”

– Max Horkheimer, Eclipse of Reason

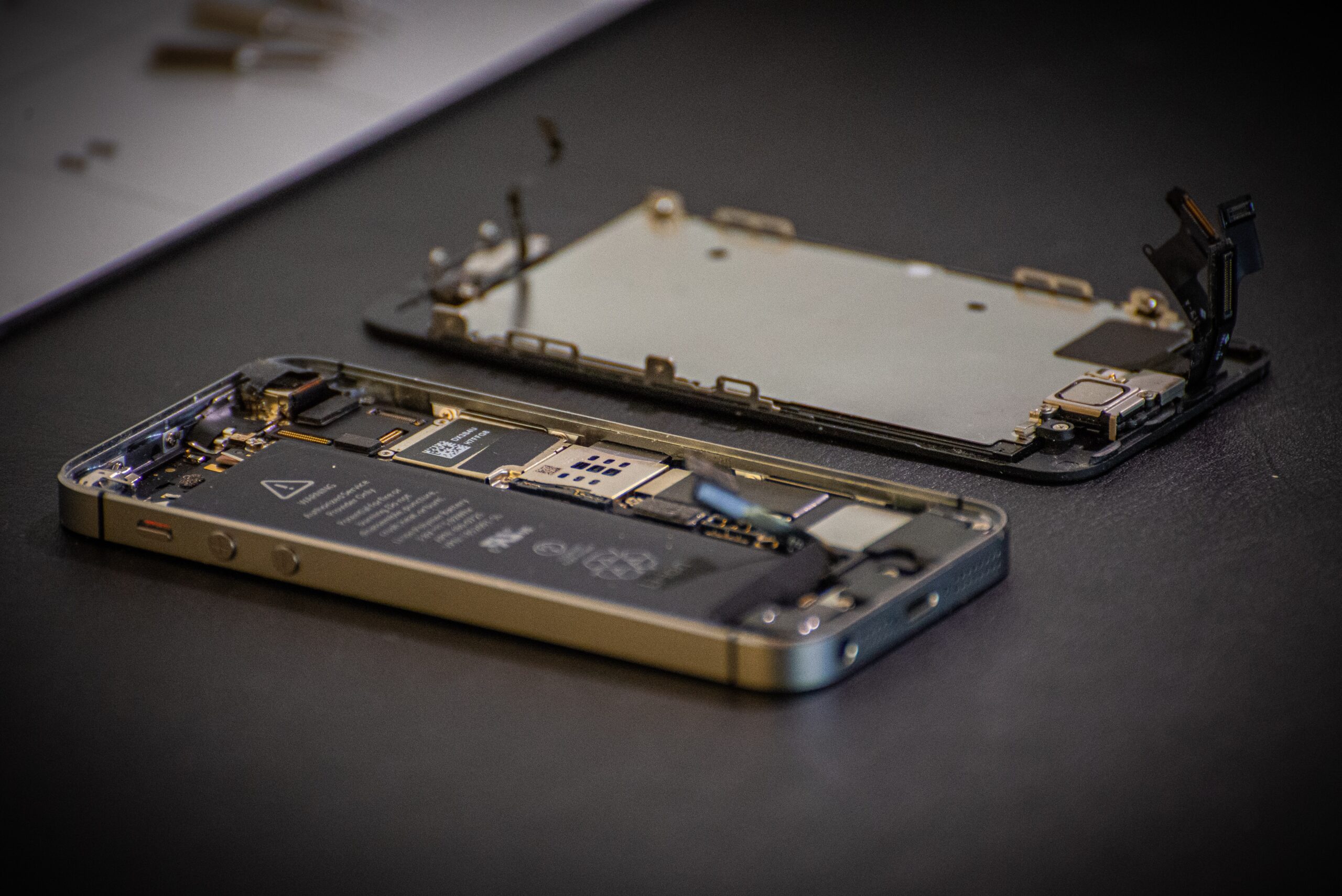

This week I repaired my iPhone 7 for the fourth time. It was the front-facing camera that had lost its verve, along with a torn ribbon cable. Before that it was a cracked display, and before that, a worn-out battery. Usually when a smartphone breaks we are faced with the inevitably frustrating choice between paying for it to be repaired or simply replacing it at significant expense.

I’m lucky to have grown up in a household where repairing things was standard procedure. My parents still use their electric oven that they bought in the mid-90’s, which still looks nearly brand new as a result of my dad’s annual ritual of pulling it out of the wall and cleaning down most of the removable components. I distinctly remember one weekend awhere I was given free rein to disassemble an old VCR machine and get a closer look for the first time at those cityscape circuit boards hidden inside the body of that typically bulky 90’s recording hardware. Micki Kaufman, a former fellow here at the GCDI, has also covered the childhood joys of tech-wrangling with much more compelling detail.

Twenty five years later, the kind of technology that we find ourselves needing to maintain most often has been miniaturized almost completely out of reach. Televisions and computer monitors sealed into plastic cases with glue rather than screws, kitchen appliances with burned out components that can’t be replaced, and most notably– the undisputed heavyweight champion of planned obsolescence– the arrival of the smartphone, 151 million of which end up in landfill every year in the US alone. Gains in efficiency and power have given each of us thousands of hours of saved labor, but it has also separated us from an apprehension of the mechanics of common interfaces in daily life. With a kind of amnesia for the spirit of engineering, we are drowning in a bumper crop of technology and yet we are starving from lack of technique.

What you learn when you repair an object is that your intelligence shapes your experience of the object. Summoning the courage to dismantle, tinker with, and carefully maintain a complex object transforms your role from passive consumer to active co-producer of the technology at hand. The difference is precisely like that of becoming a writer after many years of being only an enthusiastic reader. One might be surprised to learn that the battery of a Macbook Pro looks like four iPhone batteries wired together in a kind of lithium-ion daisy chain. The oddities of contemporary technology engineering are only available to someone who looks beneath its pre-assembled surface.

The person who learns to dismantle and repair also becomes a keen and well-informed judge of the true qualities of a product: what may appear impressive on the outside– silky bezel glass surfaces, radiant solar flare LCD display, evergreen processor promises of chipset utopia– the skilled repairer is satisfied only after looking behind the surface at the architecture that lies behind the presentation. Georg and Dorothea Franck perhaps said it best: “The mark of quality lies in the presupposition of a very demanding, sensitive and intelligent user”.

Furthermore, what starts as the lonely disappointment of a broken smartphone inevitably broadens out into discovery of a community of skilled practitioners. Thanks to online forums and tech-repair bloggers, one learns that the journey, thankfully, is not at all unique. The movement that is now known as the “right to repair” has gained momentum in recent years and is now culminating in multiple legislative efforts across the US to enforce the provision of repair documentation by manufacturers, as well as Original Equipment Manufacturer parts, or OEM, to consumers. In New York state the “Fair Repair” act, requiring electronics companies to provide both OEM parts and repair guides to their products, has already passed both chambers of the legislature, and is being followed closely by a similar bill covering the auto industry. The Fair Repair act itself is now awaiting approval by governor Hochul, who is now being harangued by industry lobbying groups making the claim that consumers are essentially not intelligent enough to repair their own products without injuring themselves.

Over in Europe, where your list of problems doesn’t directly include waiting for US politicians to shrug off the power of corporate interests, the dream of owning and maintaining sustainable mobile technology has become something of a reality. Fairphone, a Dutch company founded in 2013, offers the world’s first modular smartphone. You can replace individual components such as the camera and the battery while recycling old ones, and all the materials are ethically sourced, receiving FairTrade certification. What is so compelling about this company is that it fully accepts the necessity and desirability of things like a terabyte of mobile storage, or 4K 60FPS resolution cameras, but provides that technology in a way that avoids generating 60 million of tons of e-waste every year. When this phone is made available in the US, I will be first to finally trade in my Argo of an iPhone in favor of this kind of sustainable design.